One mistake being made today is a directional assumption held by data people. These people typically have the word ‘engineer’ or ‘engineering manager’ in their title, whether they are analytics, data, data platform, etc., or variants of these.

The mistake happens in the context of data democratisation. Data democratisation usually refers to allowing non-technical stakeholders access to data without help from a data person. If you think about it on a scale from least to most, the least is no access to data without asking a data person who curates a report/data pull or other artefact for you. Most would be where you had an AI system you could ask to provide anything a data person could before, on-demand and almost instantly. The middle ground is a BI tool, and even this is a sub-continuum.

However, another kind of data democratisation is at play in the context of data transformation. Historically, data transformations have been developed by data engineers or BI developers, who were often very segregated from their business stakeholders. These stakeholders eventually depend on their outputs, and a product owner/manager controls the use of these skilled resources.

This became even worse during the Big Data era, where it became even more difficult to build these transformations on unwieldy Big Data stacks than on previous monolith stacks like MS SQL Server, Oracle, IBM or Teradata. Then came the modern data stack and tools like dbt, which allowed fewer and less technical users to build their data transformations on bigger datasets than Big Data stacks could handle.

Jumping off from this point, the obvious next step in data democratisation in terms of transformation is to allow data users with even less technical skill to make their own data transformations. The analytics engineers of the MDS era, whether from data engineering, software engineering, analytics or other non-technical disciplines, were inclined to pick up and learn how to use technical systems. They had to learn git, shell, dbt, SQL and Python, and they really had to be comfortable with them, or at least a subset. They also had to be inclined to enjoy this work.

This all meant that the IDE was the right tool for them to use for data transformation. Like many others, the first IDE I used for data transformation with dbt was VSCode1, and, even today, I still use it even in the guise of Cursor, Windsurf and whatever the next VSCode AI fork of note will be2.

Software engineers often prefer IDEs in the terminal like Vim, Neovim or Emacs, but this is probably a step too far for data engineers unless they have come from these disciplines and continue to use the same tools. The software engineers who don’t use terminal IDEs pretty much all use VSCode or Jetbrains. Data and analytics engineers who have come directly into the field3, or from somewhere other than software engineering, predominantly use VSCode.

Now, we come to the mistake: to allow an even broader set of people to do data transformation work and democratise it further, we need an easier IDE. After all, setting up VSCode, checking out repositories, learning git, managing environments, and dealing with Python dependencies… makes it daunting for these less technical data users to build data transformations.

What if we had an IDE that dealt with environments for the user, that simplified git, was browser-based, requiring no installation or setup, and had all the commonly-used packages installed? Surely this would be the right IDE for these less technical data folks?

But therein lies the mistake. These less technical data folks are not quite like us. They aren’t inclined the same way. They don’t yearn to be software engineers; they have only become more technical to continue to do the job they love doing. They’d be perfectly happy to stay just inside a BI tool… to be honest, they were even happier staying in Excel, but damn that pesky row limit. Index match was already a step too far, let alone an inequality join. They prefer Dell XPS to Macbook Pro. They prefer ease to flexibility. They think of the command line as something from yesteryear, where you had to start Windows from.

They don’t want to tinker with an IDE; they don’t necessarily want to code at all. They don’t enjoy this part of their roles; it’s a means to an end. They actually like being in the product/marketing/finance meetings all day; they like talking to stakeholders. They prefer talking to people to talking to computers. They’re not like us. So why would we think they just need a helping hand to use a tool similar to the one we like?

We shouldn’t have started at Vim and walked forward; we should have started at Excel and walked backwards. In my recent series on SQLMesh, the IDE was the one thing I was sure was a mistake. I’m sure because it’s the same mistake dbt Labs made when they spent years working on the IDE. The problem with these baby IDEs is they come from a position of technical superiority from engineers: “Look, you’re not capable of using the real thing, so here’s something even you can use.” It’s still not what they want. We’ve made a mechanical Aeropress as a solution for people who want a push-button coffee machine.

The reason they like Excel is because it’s visual. You make a change, and you can see what it affects and build upon it. A mathematics notebook that does the arithmetic for you. You don’t need to render a DAG from the code or generate column-level lineage; you build the DAG and the lineage directly in the visual.

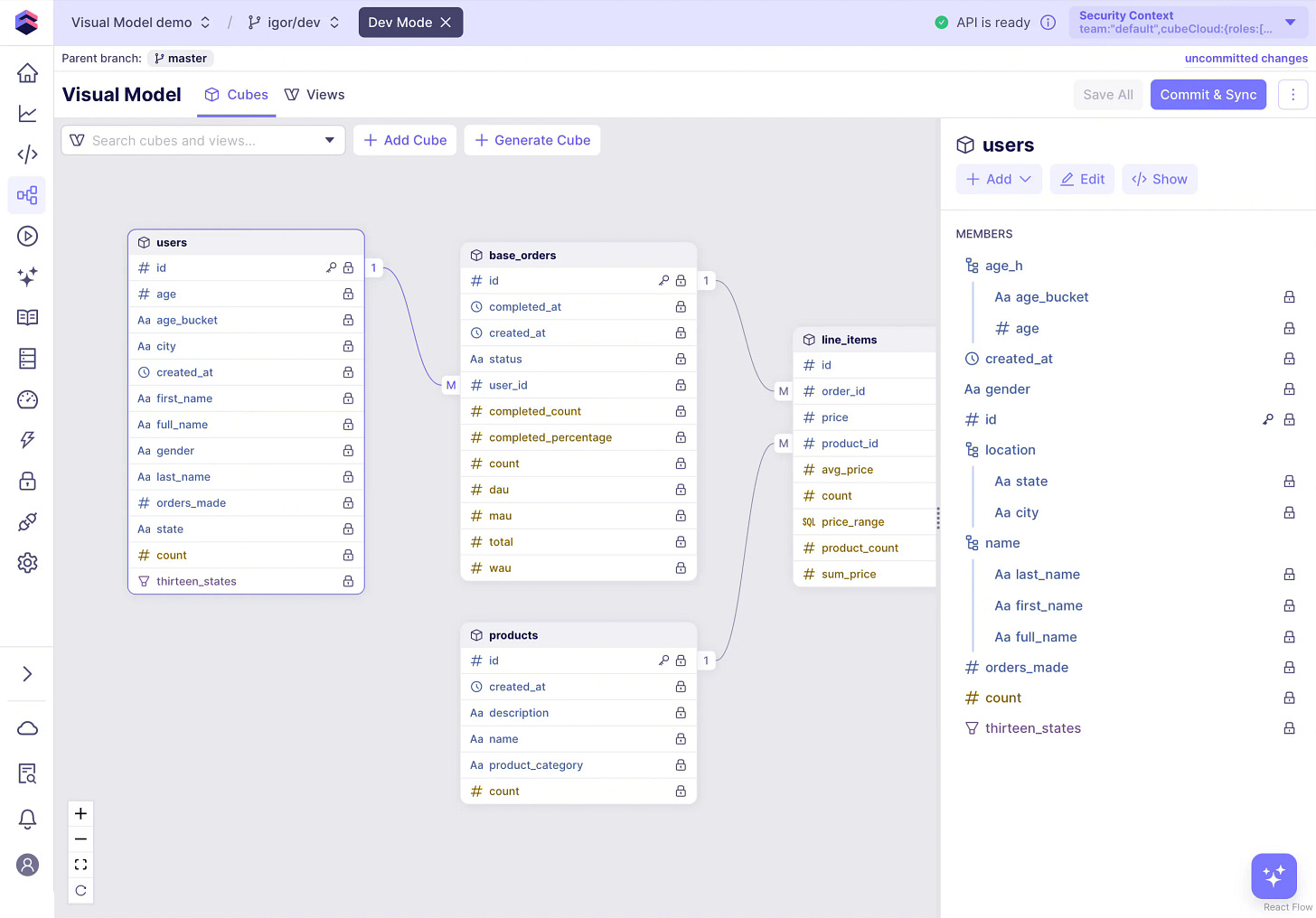

Large enterprises have long had a substantial community of data users who wanted to work in this way and were difficult to retrain to learn how to code and hadn’t ever really needed to in the first place. This is why, when companies switch to building for the Enterprise, they build visual ways to do things. This is why Coalesce.io started this way and why dbt Labs have now built visual ways to build. Even if these ways are simpler and not fully featured, that’s probably good for folks who want less complexity in tooling.

The problem is that it makes it harder to collaborate with those who still work in code. The tool needs to generate code as an output of the visual build. This code still needs to be reviewed by more technical data folks, who then resent the quality of the code because it wasn’t coded in the first place and we don’t get the context from the visual builder when we have to review the generated code.

It’s also common for visual tools to not generate any code at all. Usually, code-first data folks then ignore any work done in them and say it isn’t governed.

It feels like there is no viable compromise. If you’re technically minded, you will eventually want something as fully featured as VSCode; if you’re not, you want to build visually. Those stuck in the middle are only temporarily there, if by choice, and otherwise are forced to be, which is not conducive to collaboration. It’s very common for about 50% of seats assigned for these simplified IDEs to remain unused, and most of the rest are rarely used.

Could a middle ground exist, where visual and code building can happen in the same place? Where code-first data folks can work alongside less technical ones to allow them to understand and contribute to data transformation? Maybe this feature from Count.co4, which was always intended to be a collaborative analytical space between stakeholders and data folks, could actually be a collaborative data transformation space between code-first analytics/data engineers and visual-first data folks.

Even though there is no Excel-style grid here, it was always like the grid in your maths notebook… there to help you. There was no reason the values and formulas couldn’t have floated in a canvas space, other than simplicity5. For decades, these visual data folks have used Excel as a structured canvas to do data transformation at a small scale. This is what they’re used to. So if we can allow them to continue to work like this, alongside code-first data/analytics engineers, with frameworks like dbt/SQLMesh enhancing but not imposing on the process, with version control quietly happening, with collaboration… is this the real ideal IDE for them?

I briefly used Atom before it, until someone told me it had been discontinued and that VSCode’s community extensions were much richer. Not being overly opinionated, I switched and am glad I did.

There is no reason to be loyal (I could probably write a blog post with that title), and there is almost no switching cost between VSCode forks. All the extensions still work, but the keyboard shortcuts are the same, or can be set to be (I don’t change them for this reason). This is one key issue in companies with VSCode forks as a product: there will always be a next hot fork coming; it’s easy for your users to switch, so you’d better innovate at great speed. This is why every time I cmd+tab to my Windsurf windows, there seems to be a new update available. They can’t stop moving, or they’ll die like sharks.

Yes, today, there are people leaving universities with analytics and data engineering degrees/masters, and so are coming straight into the field instead of from somewhere else, which was always the case when I started out. 👴

I have no financial interest or otherwise in Count.

If you merge cells, resize rows and columns, and change border styles… you can create a document that appears as a canvas in Excel.